I’ve been a fan of text adventures since I was about 12 years old in 1983. I basically learned English playing them (and reading my neighbour’s American Mad Magazine issues), so they always had a place in my heart.

Very briefly, these games describe the story as text and take text input from the player to progress. A typical exchange might be “You see a closed door.” – “OPEN THE DOOR” – “You open the door, revealing a hallway.” Since it is never explicitely stated what options exist in a given situation, this is widely regarded as a series of problems to solve, even though that might not be the intent.

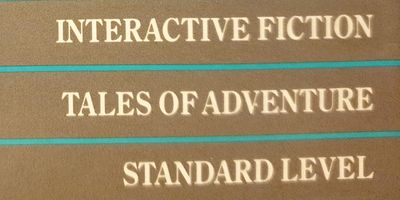

Infocom, one of the most important and respected producers of text adventures, started calling their mostly story-focused products “interactive fiction” to distinguish them from the usually terse and mainly puzzle-oriented games that made up the bulk of those games. The term stuck, and from the late 80s onward, was used synonymously with “text adventure” for this type of game. Sometimes it was reserved for the more sophisticated games, but as the whole genre shifted to an increasingly literary approach, so did the use of the term, often in its abbreviated form “IF”.

Around the turn of the millennium, there was a lot of discussion about text games as an art form, and some experimentation with different ways of presenting them. Up to that point, while there had always been serious attempts of telling an interactive story, and the idea of “puzzle-less” IF had gingerly been explored, interactive fiction had remained in the form given above where the player would type phrases, and pieces of IF were generally regarded as games, albeit sometimes with a serious theme.

Some of the discussions during that time incorporated interactive books, such as the well-known Choose Your Own Adventure series or the more game-oriented Fighting Fantasy books, into the broader term “interactive fiction”, and there were a few attempts of assembling programming libraries to help create games in the same format with the tools of the time.

Games of that type list a number of options and progress the story through choices between them. The exchange above might have a form like “You see a closed door. Would you like to 1) open it, 2) kick it in, or 3) ignore it and continue searching the room?” Obviously, this presentation does not lend itself to puzzle-solving quite as directly: there is never a question of the current options.

This is where the lines start getting a little blurred. As “interactive fiction” was not as clearly defined a term anymore, it became necessary to qualify what type of IF was meant: “parser-based” – the parser being the part of the software that turns typed sentences into actions – or “choice-based”.

Neither those people who prefer parser-based works nor those who prefer choice-based works generally see a need to clarify this preference in discussions: the core concept of a story being told and the player interacting with the narrative is the same in both cases, and there is no enmity between these groups.

However, as the available tools were getting more versatile, works with graphics, sound or mouse control were released, and an altogether new kind of interactive fiction emerged, nowadays mostly called “visual novel” (with interactivity being implied, as opposite to a graphic novel that is usually non-interactive).

The term “interactive fiction” that started out meaning a very specific thing has now become virtually undefined, encompassing hyperfiction experiments of the late 1960s and 70s, text adventure games, puzzle-less interactive stories, graphical works, choice-based works and even visual novels with no descriptive text at all. Espen Aarseth introduced the term “ergodic literature” to replace “interactive fiction” as a textual medium, but this has an even broader definition of interactivity as a theoretical construct.

It will be interesting to see the further adventures of interactive fiction, pun intended, especially from the perpective of having played early text games and witnessed the evolution of the term and the medium to their current state.

The featured image was taken from the box of Infocom’s Cutthroats.